During the first months of the war in the Pomeranian province, Poland, many people were murdered during mass executions, including priests, teachers, politicians, members of the Polish Western League, merchants and civil servants (e.g. postmen, policemen, border guards), to mention but a few. The bodies of the victims were buried in mass graves in order to cover up the evidence of the crimes. During the bloody autumn of 1939 executed were also disabled people and members of the local Jewish community. Nowadays it is estimated that between September and December 1939 circa 20,000-30,000 Polish citizens from the pre-war Pomeranian province were murdered. This was twice as many as the number of all the victims from other parts of pre-war Poland. This is why some Polish historians have recently named the crime – the Pomeranian crime of 1939. It was a prelude to a later mass killing during the Second World War.

Our main research hypothesis is that that the mass scale and character of mass killing in 1939 in the pre-war Pomeranian province means that there are still many records of the crimes undiscovered. It is hypothesized that the combination of methods, data, and perspectives (history, ethnography, archaeology) will enable to uncover new aspects of these mass massacres of 1939 as well as the contemporary value and significance of this dark heritage. This is why this project pays attention to the past and present of the problem. In other words, the past and its contemporary value will be the subject of scrutiny.

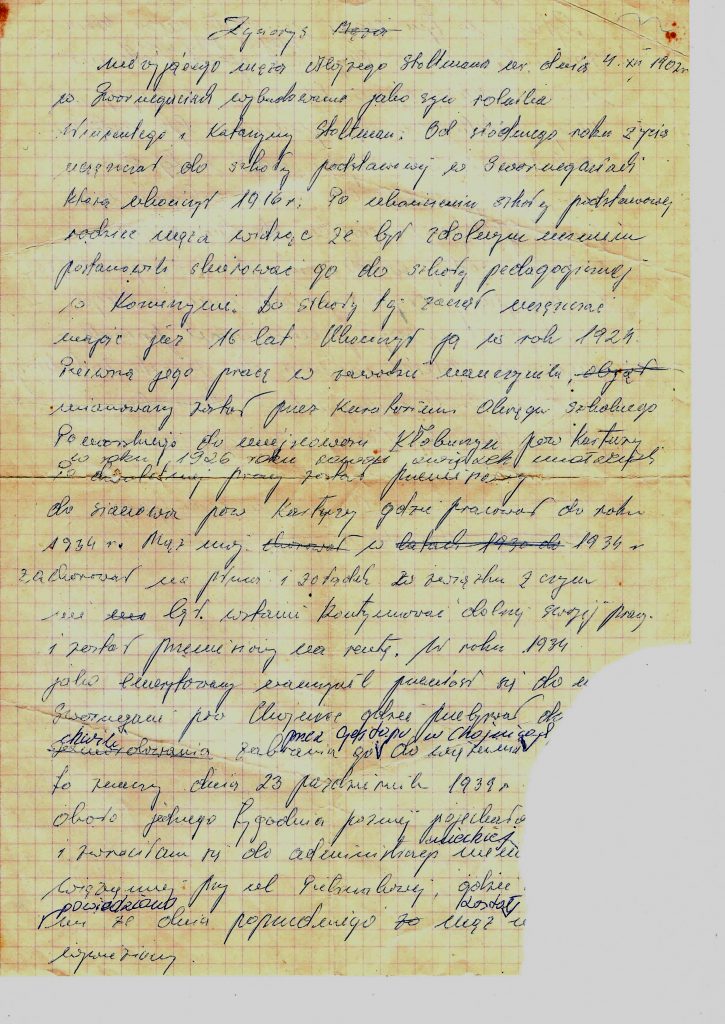

Indeed, there were approximately 400 places in Pomeranian province in 1939 where Germans executed Polish citizens. The idea behind the project is to research in detail the past and present of heritage of selected four sites related to the Pomeranian crime. This project does not aim to simply discover mass graves but rather focuses on manifold heritage of the Pomeranian crime in the province. That is why part of ethnographic research will be documenting monuments, memorials, spaces of imprisonment, itineraries of displacement, spaces of killing and burial related to the crimes and their contemporary role, meaning, significance. The same concerns family memorabilia kept by the relatives of the victims (and sometimes by local museums, houses of cultures, or amateur historians). These objects might be very interesting from archaeological, historical and ethnographic perspectives in terms of memory devices – as material bridges between the past and present, between the dead and the living. The use of historical, archaeological, and ethnographic approaches will inspire and influence each other.

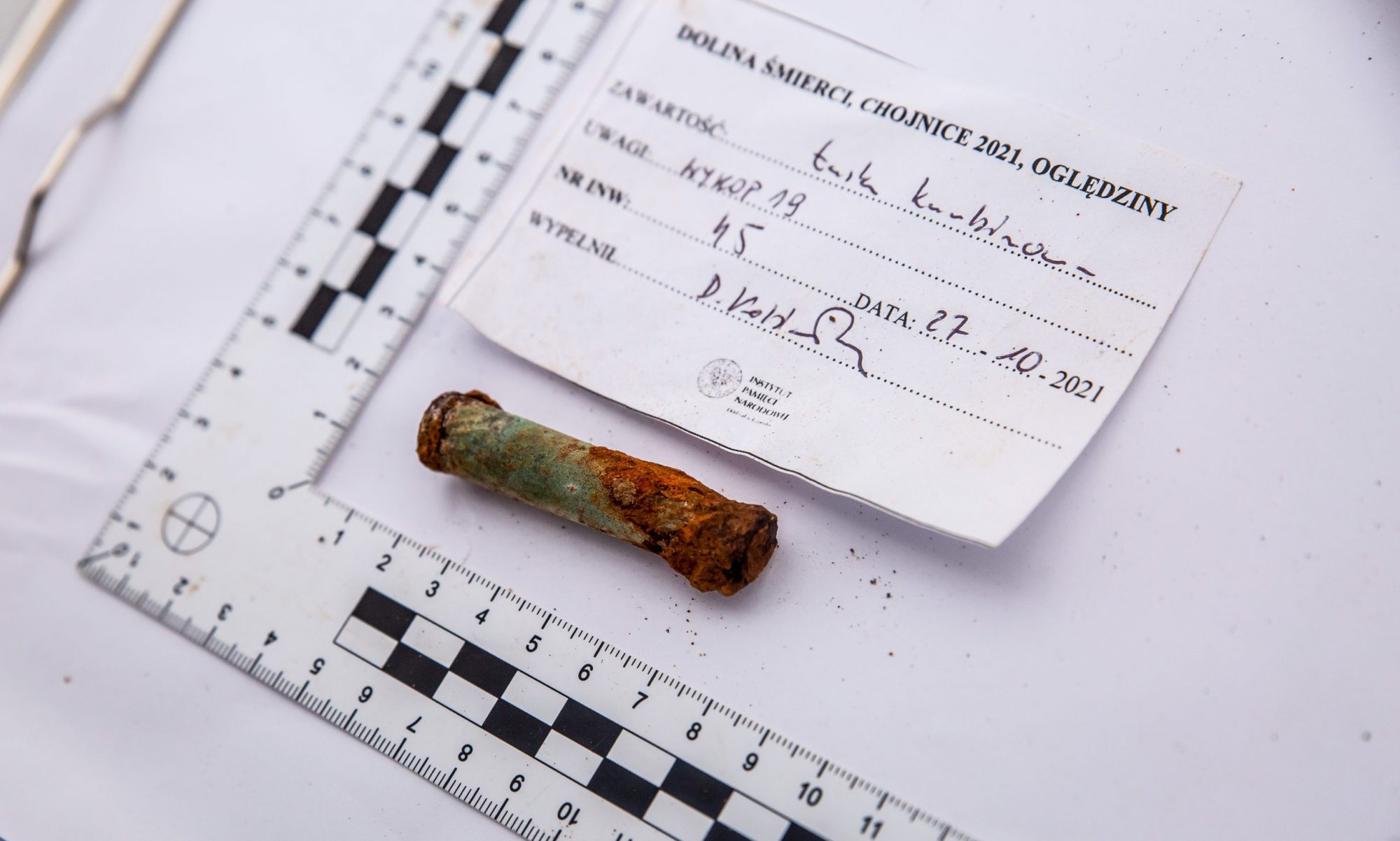

Some of sites of mass killing and mass graves from 1939 were exhumed after the war. However, these exhumations were usually supervised by civilians rather than archaeologists. The documentation from the exhumations is imprecise and very general. The exhumations were undertaken rapidly to discover the bodies of the victims and move them to proper cemeteries. Long bones and skulls were usually removed, but many smaller bones were left behind. The same can be said about personal belongings and other characteristics material culture related to mass killings, such as bullets and shells.

No one was really concerned about them during the 1945 exhumations. However, sites of mass killings are crime scenes. From this point of view, every piece of material culture is evidence of the crime. From an archaeological point of view, sites of mass killings can be researched as a specific kind of archaeological site. In this approach, every bullet and shell is seen as part of the archaeological record. Bullets, shells, personal belongings of the victims, bones of the victims, dimensions of graves and exhumation pits can be as informative as other kinds of historical evidence. Through these small, rusted, broken objects etc. we can reconstruct some of the crucial aspects and heritage of the German mass killings in 1939 in the pre-war Pomeranian province. Here archaeology is actually a way of collecting evidence of the crime – forensic archaeology.

To sum up, the significance of this archaeological project lies in researching sites related to the Pomeranian crime of 1939 that have been out of reach of archaeological scrutiny in Poland to date. We make this scrutiny possible through the integration of data obtained by the use of a variety of noninvasive and invasive archaeological methods and their analyses in comparison to the existing historical, oral, visual, and material records.